WELCOME

This is the home page of two international interdisciplinary conferences held in Cambridge, at the Cambridge Conservation Initiative and Pembroke College.

The first, ‘Owned by Everyone: the science, poetry and plight of the salmon’, was held in December 2019, at the close of the International Year of the Salmon, and was made possible by the support of Pembroke, the CCI, Salmon & Trout Conservation and Patagonia. Delegates came from Alaska, British Columbia, the United States, Norway, Sweden, Ireland, Scotland and England, inspired by a shared passion to understand and do all we can to protect wild salmon and to persuade others to join us. It was a unique gathering of fisheries biologists, anthropologists, poets, anglers, conservationists, behavioural ecologists, environmental historians, literary critics, a folk singer, a member of the Sami Parliament, and representatives of the NGO members of the Missing Salmon Alliance, and of the research, experiences and stories of the salmon they brought to Cambridge from across North America and Northern Europe. Its achievements were considerable, and include the reassessment, funded by Salmon & Trout Conservation, of the Atlantic Salmon for the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species. The last assessment was in 1996; the results of the reassessment are due in July. Other work is still very much in progress. Since we met, and acting on horrifying images of the impact of salmon farms on wild salmonid runs, both in Norwegian fjords and on the West coast of Scotland, WildFish has continued its campaign against salmon farms and has launched Off the Table, which seeks to dissuade leading restaurateurs from serving dye-injected salmon from Scottish salmon farms. Some Cambridge Colleges, including our hosts, Pembroke, no longer serve farmed salmon. But we still need massive injections of investment in closed containment units, which can meet the needs of urban populations and restore wild salmonid runs to their glory on the West Coast of Scotland and indeed in Norway. See the blog post ‘Slutprodukt’, in the menu to the right of this page, for more details. Or view ‘Wild Fish’, online or here.

Owned by Everyone?

The second of our conferences, ‘Owned by everyone? The wonder, plight and future of chalk streams’, was originally planned for March 2022 but then postponed by a year as a result of the Omicron variant of COVID-2019, eventually taking place on 30th and 31st March 2023. It has been at least two years in the planning, by an organising committee that, via Zoom, brought together the complementary expertise of WildFish Conservation, in the form of its CEO and its deputy CEO and Head of Science and Policy; the Curator for the Arts, Science and Conservation at CCI and a senior advisor for strategy at BirdLife International; and the Chair of the Ted Hughes Society (and author of the recent book The Catch: Fishing for Ted Hughes). Supported once more by the CCI and Pembroke but this time, too, by the Impact Fund of the University of Cambridge’s School of the Arts and Humanities, and organised as in 2019 with our partners WildFish Conservation – you will come across the story of their name change if you read and listen on, and follow links to the eight podcasts we will be making in the weeks to come if you check back – our gathering in Cambridge this time reflected the geographical range of the world’s two hundred and twenty chalk streams. Eighty-five percent of them flow, when we let them, in England, between East Yorkshire and Dorset.

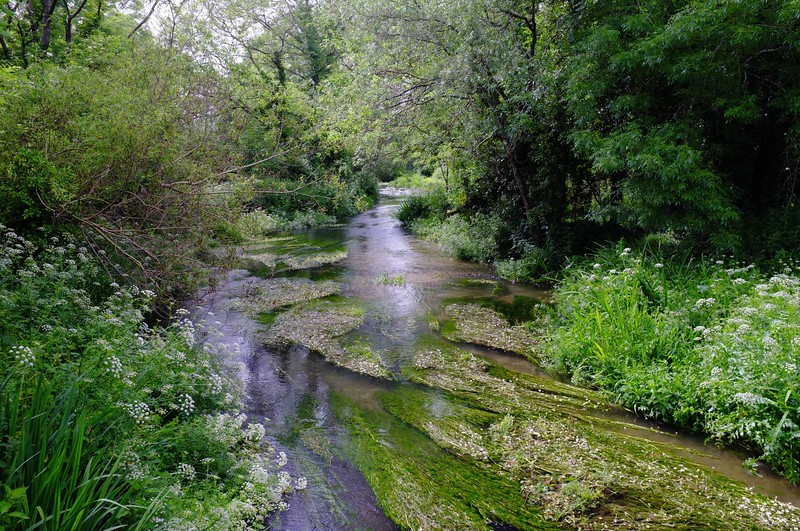

Chalk streams in summer and autumn. Images Charles Rangeley-Wilson

Chalk streams are one of the rarest and richest ecosystems on the planet. They’re as rare as Rhinos, but much, much more English. And they’re also much less obviously wild. Managed as they were between the Neolithic period and the Second World War, chalk streams are equable, fed by chalk aquifers in ranges of hills formed, sixty million years ago, when shallow seas dried up and left deep layers of shellfish, through whose rock rain takes months to percolate, becoming mineral-rich in the process. The temperature of their lucid water is as constant as, left to their own way across flood plains in gently sloping valleys, their course is sinuous. Tresses of wonderful vivid greens and whites of ranunculus, water-crowfoot and starwort shelter astonishing varieties of invertebrate life, which, before the most beautiful of the river flies take flight to dance above them, in turn feed fish – a genetically distinct subspecies of salmon, sea trout, brown trout, grayling, bullheads, alongside resident minnows, bullhead, perch – and all those birds and mammals that feed on them. The kingfisher and otter are their elusive, camera-shy stars.

A chalk stream and its banks in full bloom. Image: Charles Rangeley-Wilson

These places have long spoken to writers and artists. Millais’ Ophelia floats on a chalk stream. Kingsley’s Water-Babies swam in one not unlike the Cam where, staying at Duxford Mill, he wrote it. The friendships in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows all unfurled on a chalk stream. And Ted Hughes, the inspiration for both these conferences, and a constant reproach to the reversals in the health of our rivers and thus of our national consciousness since he battled for and fished in them and wrote out of the depths of the self and the wild he found in rivers in the 1980s and 1990s, once described his reverence for their waters and for the culture and traditions they supported. ‘Owned by everyone’ was a phrase he gave to a salmon smolt to sing, in the first poem he wrote as Laureate, to raise money for the Atlantic Salmon Fund, in the same month that he wrote a letter to the doyen of dry fly fishing on the elite southern chalk streams that would, within a season, open their mysteries to him. And these rivers are still inspiring the most mesmerising and simplest of pastimes. Try this thought experiment. Take a sheet of acid-free paper. Paint it in acrylic red and let it dry. Then set it adrift on a stretch of river overhung with trees and fringed with grasses and with a plan in mind for fishing it out before it disappears under an old bridge and follow it downstream. Or just watch artist Kate Measham’s drifting paper:

Who saw this, mesmerised, in Cambridge? A company that represented almost the entirety (except for a Normandy contingent) of the world’s chalk streams. There was a guardian of Denmark’s chalk streams among us, alongside an otherwise English assembly of activists, river keepers, water chemists, environmental lawyers, illustrators, conservationists, fishermen, artists, kayakers, wild swimmers, politicians, community groups, writers, artists, underwater photographers, and that folk singer, again, back to listen this time. We weren’t as young as we liked, though there were undergraduate and Master’s students among us. But we were united, all, by one condition: we are all adult children, whose sense of wonder and reverence and love for these rivers keep on refreshing us, who want to pass this on to our own children, and to theirs. To everyone, in fact.

Yet Kingsley and Ted Hughes – and, for that matter, the closest of Hughes’s friends, Irishmen Barrie Cooke and Seamus Heaney – also knew that the heads and hearts of children of all ages could feel horror as well as wonder in the same moment, with almost the same cause. Kingsley’s Tom was a chimney sweep, in the course of whose adventures under water we meet Mrs Doasyouwouldbedonevy and Mrs Bedonebyasyoudid. Kingsley himself published his marvellous essays ‘Chalk-Stream Studies’ in May 1858, within three months of the largest chalk stream in the world, the Thames, falling victim, along with Parliamentarians and the rest of London attempting to do business or just avoid cholera from polluted water supply, to The Great Stink.

Sounds familiar, eh?

It needs to. We need, as Hughes knew, in his horror story for children of all ages The Iron Woman (1993), to be touched by this crisis ourselves, as Lucy and Hogarth are in that powerful fable, to hear and be horrified by the screams of the creatures of the river, who, for most of us, suffer at and with a frequency that has, for the last decades, left most of us unaware of the direct connection between their plight and ours. Hughes had long seen that connection, knew ‘the recently-discovered not to say revolutionary truth – what you pour down the drain reappears in your cup’, even if, when he wrote those words over a decade before The Iron Woman, he’d been advised not to include them. They were too gloomy for the essay he was writing. But he came to know when was the time to speak out and marshall – ‘martial’, as Hughes spelt that word – public opinion. This last year, there’s been a groundswell of outrage growing at the horrors that we see reported almost daily. We live in times when water companies abuse or ignore their statutory obligations not to discharge untreated sewage into our rivers except in extremis, and when the food additives in our daily diet contribute 20% of the phosphate pollution that, along with agricultural pollution, road run off, our dogs’ flea treatments and massive exploitation of licenses to abstract water for domestic and industrial use, is hastening the death of these green crown jewels in our culture as well as our ecology – and remember that the Greek word at the heart of ecology, oikos, means home – we need to be reminded of some home truths, bluntly stated. And ‘we’ need to grow, to wise up.

It’s a devastating quirk of English law, and certainly not one that affects Scottish or American rivers, say, or rivers where indigenous peoples like the Maoris still have an influence on the conduct of parliaments, that every inch of English rivers is owned by someone. There’s a difference between secret places (a tunnel of trees hanging protectively over trout-dimpled runs that the swimmer or kayaker or angler discovers and thrills at as they round a bend and come up for air, plunges down for water, and knows they’ll have this moment to draw on their whole lives) and private places, trespassers-will-be-prosecuted, keep-out places. Should the rivers that flow through these wonders at all seasons be granted the rights we accord, on a reflex, to people, and now with only a little more thought, to animals? At least one of our speakers thinks so, thinks rivers should be owned by no one. When you listen to him, without the distraction of any slides, in free flow, in the third of our podcasts, you might be convinced. Recent case law suggests that environmental justice, environmental democracy – our stake in our chalk streams, before over-abstraction reduces their flow to a toxic trickle and then to dust – not to mention a sense of enlightened self-interest (in our health, in our children’s health, their children’s; in our wellbeing, our sense of ourselves as bodies in an abused exploited world that, as a species, and a nation, we can still act to save) — demand change, not least from the agencies that are supposed to abide by the law but palpably, demonstrably, haven’t. We need radical, informed, change before it’s too late. As another of our speakers observed, out of love and experience and fear at what is coming, ‘Our rivers are half full. Very soon they’ll be half empty.’ The River Ivel in North Hertfordshire used to support four mills, built in medieval times, when buildings like mills needed to rely on the enduring certainty of their income streams. Now that massive and prolonged abstraction by the local water company has reduced the water table in the chalk hills by between six and eight metres, those mills stand dry.

‘The river’s tent is broken.’ Ted Hughes’s words, about the natural changes a season brings to a valley and its trees, have become a bleaker truth in the forty years since their publication. We need to fix it before that flimsy translucent roof falls in. ‘We’ here means people who have in the past tended to regard rivers as so important to them, to their own sense of release or relaxation or absorption or renewal, that others who have gone to rivers for their own purposes, or who don’t think of going to rivers at all, that the needs of these other people, or even the needs of the river itself, as an ecosystem that, left to itself or at least restored to how it was, very recently, a matter of decades ago. This sense of exclusive access needs to change, to admit others, not to every mile of every river, but in different seasons and on different stretches according to the river’s needs, not to ours. The days of interested parties need to end, soon.We need, instead, to build the broadest and most knowledgeable and passionate coalition of care, with nobody pissing out of, or into, the river’s broken tent, unless we are sure exactly where our waste water goes.

That is: we need to make use of the environmental protections and statutory obligations that have been on the books for most of our lifetimes, however old we are. Before they disappear, as many, many are due to in the lifetime of the current Conservative Government, at the end of this calendar year, indeed. Where, quietly, environmental protection has been ‘ditched’, this year, so quietly indeed that only three of the eighty or so knowledgeable committed experts in the seminar room at the Cambridge Conservation Initiative at the end of March knew that the Government’s long-standing requirement to report annually on water quality stands now longer, we need to create our own Great Stink until this gross abuse of existing responsibility to the natural world, to these enduringly surprising Wild Isles of ours, has been reversed. (Do please watch the freshwater episode of Sir David Attenborough’s series Wild Isles, first broadcast the weekend after the conference. And, when the fifth episode has aired, go to iPlayer to watch the sixth, which won’t be, to catch Sir David’s plea for swift action. Watch Paul Whitehouse’s Our Troubled Rivers, which concluded the weekend before we met. And listen to, or read — we hope to post a recording, or a text, here soon — Feargal Sharkey’s brilliant impassioned speech at Pembroke College on 31 March.

In an article in November 1992 for The Observer, entitled ‘Your World’, Hughes wrote:

all our urgent talk about environmental problems seems to get us nowhere. Many sporadic local recoveries and advances do not reverse the cloudier, global, steady deterioriation. Resonant promises from politicians and the glossy environmental policy brochures of industry seem to miss the mark. There is something about debate itself, about the endless demand for further research, that is a substitute for responding truly to the situation. Nothing about it changes the way we actually live. Verbal argument simply provokes more verbal argument. What is needed is a new kind of language that goes straight to the heart and soul, and changes things there. When we change here, then everything has to change, our whole way of life simply changes, and it can change quickly.

At the end of our two days in Cambridge, the experts drawn together from their different specialisms and professions in defence and love of our chalk streams felt as well as knew the truth in Hughes’s words. And we are at work on a closing statement (this emboldened phrase will become a link when we’ve agreed the text( that will reflect this and be a call for action, for change, and quickly.

But we also know we need your help, everyone’s help, for change to happen, and with it all the attendant changes in our own ways of life: in our attitude to water, in our sense of its value and cost. In the planning system: can it really be the case that agricultural licences to abstract water from a local river, once granted, are unlimited? Can it really be right that housing developers and even those designing nuclear power stations can expect already dangerously, even terminally depleted rivers to meet their needs, their greed, our naive complicity in it? Look at the results: a river that lives up, or down, to its name.

We need, everyone needs, to be more than enlightened in their self-interest. We need the next generation of water users, water bill payers, to know more than their elders do about the cost and value of water: about the false economies we have as a country sleepwalked into making, compared to other privatised utilities. (You can at least shop around in sourcing your electricity supplier: you’re stuck with your water company, and the choices its directors make in putting the needs or appetites for dividends of its shareholders — surprisingly often continental European pension funds or energy suppliers, in countries that charge far more for water and sewage than we do in England, ahead of the need to invest in infrastructure: fixing leaks, building reservoirs (did you know that that the newest reservoir in England was opened in 1989, on Ted Hughes’s watch? Remember the NRA? He had great hopes for that.) We need, as interest groups, as individuals, to be what England has forgotten how to be: resourceful, ingenious. To come together in a common interest, which is of course our rivers. As one of our speakers began his presentation by asserting, in a claim that sounds more revolutionary than it becomes on reflection, A culture is no better than its rivers. We — our memories, our habits, our appetites, our aspirations, our consumption, the objects of our worship or fear — are culture. Using the best of experience — and this website will be sharing good experience to share in the coming weeks — we need to learn when to step back from the temptations to use rivers as ours and not think of the downstream consequences. To let them be. And to find other sources, make the huge investments of money and imagination, to ensure that political short termism – not just NIMBYism but NIMTOism, that is, Not In My Term of Office-ism -stops. And stops now. There is a politics and economics of water and the electorate needs — to coin a phrase – to seize the agenda, take back control.

In the coming days and weeks, we will be posting every single session, every single presentation, every urgent half hour of question and answer, and every minute of the open discussion that brought our two days to a climax, as podcast episodes, eight in all, linked to from this website, with the powerpoint presentations that accompanied most of those presentations here too. Transparency matters, not just in our waters. Flow matters, not just in the sinuous bends and riffles and clear gravel spawning redds that so many of the experts we heard from have done so much, so lovingly, to restore. It matters in creative responses to our rivers, like Kate’s drifting paper, or the poems or drawings or films or photographs you or your parents or your children are inspired to make. It matters in scientific discoveries like the ones two of our speakers from the IUCN told us of last week, and in the delivery of talk after talk which addressed the horrors of abstraction. There’s nothing abstract about the raids, hidden to most of us, on those great natural subterranean reservoirs, filtering gradually through those ancient shells, of chalk water. On the contrary, listening to the informed precision of the passion with which those who have spent their lives beside or studying chalk water, you will gasp with wonder and horror at what you see hear and hear over the coming weeks, or whenever you discover them. They are at once urgently topical as they are timeless.

But in the meantime, and as a starter, here, is the conference programme, with wonderful photographs by writer, fisherman and chalk stream restorationist par excellence Charles Rangeley-Wilson OBE. Read it, please, and then watch this space. Which we hope will become, in time, and with your help, a forum, a network, for good ideas from local rivers as for the kind of citizen science and monitoring that WildFish Conservation and many of our speakers have been practising for years. Owned by everyone? Help us rub out the question-mark.

ABOUT THE HOSTS

Pembroke College Cambridge was founded in 1347, and is the third oldest of Cambridge University’s 31 Colleges. Its distinguished alumni number world-leading scientists, politicians, musicians and poets, amongst them the poet, fisherman and conservationist Ted Hughes (1930-1998).

The Cambridge Conservation Initiative is a is a unique collaboration between the University of Cambridge and leading internationally-focused biodiversity conservation organisations clustered in and around Cambridge, UK. Based in the University of Cambridge’s David Attenborough Building, its reach is global, and it builds networks between scientists, conservationists, artists and the general public through a number of events and publications.

WildFish Conservation, formerly Salmon and Trout Conservation, is the UK’s only independent charity campaigning nationally for the protection and healthy habitats wild fish need.

————————————————————————————————————–

OUR 2019 CONFERENCE OUTLINE

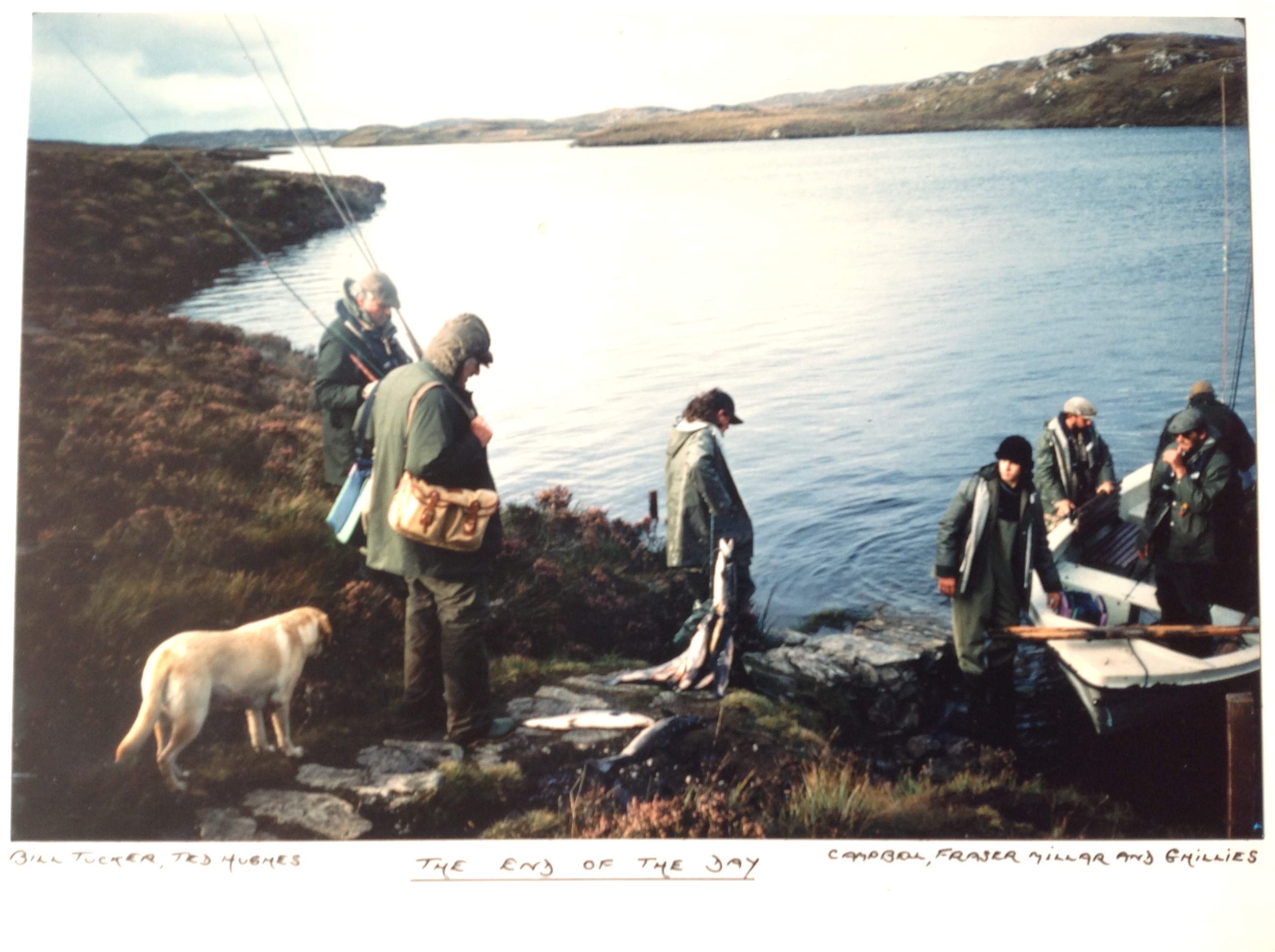

Our first conference, on the science, poetry and plight of the Atlantic Salmon, co-hosted by the Cambridge Conservation Initiative and Pembroke College Cambridge, and convened with Salmon and Trout Conservation, was inspired by the example of the British poet, environmentalist and by his own admission ‘obsessive salmon fisherman’ Ted Hughes (1930-1998). For over thirty years Hughes dreamed and caught and wrote of salmon, raising his own voice and pen in their defence. ‘I offered all I had for a touch of their wealth.’ The salmon smolt, he knew, is ‘Owned by everyone’: he regarded the salmon itself as ‘the weaver at the source’, not just of the rivers and seas it connects, but of our understanding of habitat fragility and responsibility for its protection.

Two days of talks on the salmon’s life and cultural significance followed Hughes’s campaigning example, generating conversations across disciplines as well as national borders, and with the aim of stimulating new action. The conference brought together those who value the salmon, from Norway, Iceland, Greenland, Canada as well as the United Kingdom: fisheries scientists and environmentalists of course, but also representatives from the polar first nations, cultural historians and anthropologists, literary critics, artists, story-tellers and fishermen-conservationists, among them at least one who has swum and filmed in a salmon cage, and four who fished and worked with Ted Hughes himself.

The International Year of the Salmon has proved that Salmo Salar has its champions. Fisheries scientists, environmentalists and anglers understand more than ever about this most totemic of creatures. They recognize the ‘thousand perils’ Hughes knew it faced, water quality, predation, pollution, and agriculture, and now climate change, throughout its mysterious and heroic journey from spawning gravels high up streams and rivers of the Northern Atlantic to its feeding grounds off Greenland and back again. But the salmon still needs a voice.

OUR CONFERENCE AIMS AND SCHEDULE

Through a series of short talks, chosen to inspire non-specialists and share their own sense of wonder at these fish, extended panel discussions, readings from Hughes’s work and from Pembroke College’s remarkable collection of the poet’s manuscripts, books and fishing tackle, our invited speakers explored the state of the art and science of the salmon, and addressed the best ways of responding to the grave dangers it now faces. After drinks and a film screening in Pembroke College, where delegates were offered accommodation, a conference dinner was held in Pembroke’s Old Library, with our after-dinner speaker the distinguished fishing writer, novelist and memoirist David Profumo, who fished with Ted Hughes. The Old Library is directly below Hughes’s undergraduate rooms — he was a student at Pembroke from 1951-54. The College now has a unique collection of his manuscripts, printed books and fishing tackle, as well as his ink-stained writing desk and chair, which sit below specially commissioned stained glass windows to Hughes’s poetry.

Our first morning began by comparing the results of recent genetic mapping of distinct Chinook populations in different rivers of the Pacific North West. Some runs are in steep decline, others thrive. Why? What might we learn from the remarkable taxonomies for salmon that indigenous cultures have developed over centuries of living with these fish? And what might these insights teach students of ‘the different tribes’, as Hughes described them, of English and Scottish and Irish Atlantic salmon? We heard of the genetic diversity of the Atlantic Salmon populations and sub-populations not just across Europe but also across the range of England’s southern coast, from the West Country to the iconic chalk streams of Wiltshire, Hampshire and the Thames.

Our attention then turned to the different habitats on which the health of the salmon has always depended, from clean spawning gravels to abundant invertebrate life in free flowing cold water streams, to the rivers, estuaries, coastal waters and oceans that smolt and mature salmon must negotiate en route to and from their polar feeding grounds. How many smolts make it out to sea, and how many are lost there? What if any human interventions can make a positive difference to these rates of survival and return? And what can we learn from philosophy as well as observation as we learn to renew and enliven our responsibility for the salmon?

Of all these habitats, it’s the river that remains the site of richest human interaction with and management of salmon. It’s where we catch them, or at least catch sight of them, in all their heroism, leaping water falls, enduring months of abstinence, moments of madness, as they prepare to spawn. Here Hughes’s own example is particularly apt. It was the rivers of Devon, Scotland, Ireland and Alaska that inspired his most memorable writing about salmon, in his collection River (1983, revised 1993) and elsewhere. The river is, as Hughes put it, ‘engine of earth’s renewal’, but his experience of fighting to save the river Torridge in the 1980s proved to him how fragile an engine it could be, how much its efficiency and the benefits to all who lived in and beside it depended on sustainable management. Inspired by the example of the Tweed, Hughes co-founded the Westcountry Rivers Trust in 1993. In the years since his death, the Rivers Trusts have done important work around the world to mitigate and reverse the impacts of the agricultural and economic exploitation of rivers. What can Hughes’s example teach us about the limitations as well as benefits of today’s catchment-based approach? And what do recent successes of a campaign to close a salmon farm at the mouth of an iconic Highland Loch fishery and catchment and so seek to halt a catastrophic decline in wild fish stocks tell us about the importance to the local economy, community and ecology of the restoration work to come?

Losing the battle to save a river is also to risk the loss of everything the salmon has brought home to mankind and a host of other fauna and flora for centuries wherever it has run: every kind of nourishment, physical, spiritual, cultural. A scholar of medieval Welsh writing, two poets from County Mayo and Northumberland and a leading folk singer and song collector shared stories, images and songs. We need to keep our heads and bodies full of wild salmon if we are to help it endure: as Hughes observes, ‘What alters the imagination, alters everything’. Tony Juniper, founder of Friends of the Earth and Chair of Natural England, chaired this panel.

And never before has the salmon been in such need of our impassioned defence, its place in our imaginations. In 1993 Hughes wrote of ‘the thousand perils’ it faced, from natural and human predators and degradation of their habitats: he wrote passionately about drift netting, water abstraction, agricultural run offs, intensive farming, salmon farms and the other obstacles we put in their paths, from weirs to surfactants. Three decades on, climate change, shifting patterns of predation, the commercial exploitation of wild fish, the horrors of sea-lice contamination of wild genetic fishstocks by farm escapees and the disastrous unintended consequences of hatchery and sticking programmes designed to compensate for the construction of barriers to the salmon’s progress upriver to spawn have left us in no doubt as to its plight.

Our second morning began with talks from a leading American fisheries scientist on the perils and politics of hatcheries, from a negotiator with Greenland nets fisheries on ongoing attempts to limit the harvest in the salmon’s feeding grounds, from an anthropologist who has worked with the Yurok and Inuit peoples of Alaska on the cultural, economic and political balancing act of managing competing claims on northern Alaska’s salmon-rich waters, and from a conservationist campaigning star of Patagonia’s ARTIFISHAL on the shocking realities of the salmon ages and the steps we can and must take to effect swift change.

At stake is not just the salmon itself, as keystone species, and the health of the ecologies and species it sustains. It is also the question of our own relationship of with the natural world the salmon expresses so powerfully in all its fragile wonder.

Two closing sessions focused, first, on the individual and spiritual benefits of fishing, and on the ways individual fisherman and women and the Sámi people have managed to sustain and to renegotiate their attitude to the king of fish over generations of declining fish stocks, and to justify fishing to themselves and others.

Finally, in a panel session chaired by the broadcaster and conservationist Joe Crowley, we looked forward, both to the challenges of saving the salmon and its habitats and to the best ways of working together to inspire the next generation to join us before it is too late. In 1992, Hughes wrote, of a friend’s successful court case to protect water quality on a tributary of the river Exe, that he had given the salmon a voice. As the International Year of the Salmon draws to a close, how can we ensure that scientists, poets, conservationists, do the same, speak in concert and make others — from politicians to consumers to school children— understand and respond to the totemic value of this silent hero?

The blog posts to your right and Wild Fish magazine above contain articles based on the presentations given, and links to key resources, including a film by David Attenborough and Salmon & Trout Conservation and the Patagonia feature ARTIFISHAL.