On 14th November, a gleam of silver in the turbid autumn of this dark year, Pembroke College Cambridge announced the acquisition of a wonderful literary archive and collection of associated artworks. At the heart of the archive are the products of a great triangular friendship, which grew beside, in and from the waters and bogs of Ireland. The friends were Ted Hughes, the inspiration for our Cambridge gathering, Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney and Barrie Cooke (1931-2014), British-born Irish expressionist artist and fanatical fisherman. The announcement was widely covered in the international press and media, but if you’re interested in an introduction to the archive, which will open in 2021, you can read and listen to Tom Almeroth-Williams’s feature on the University of Cambridge’s research pages here, or — for the story of the salmon that led to the archive’s discovery — Will Gompertz’s piece on the BBC website.

When they open in 2021, the archive and collection promise to transform our understanding of the careers of two of the greatest poets of the English language. In the meantime, events this week have also highlighted a crucial, foundational and enduring dimension to their relationship with Barrie Cooke. Hughes and Cooke were lifelong environmentalists. They believed that fishing was their contact with the earth, their way of breathing. On Monday 16th November, BBC News reported a horrifying bog slide and massive pollution incident in the boglands of County Donegal. The dark richness of a Donegal bog led Seamus Heaney to write the first of his extraordinary bog poems, ‘Bogland’, after a day spent with another painter friend T.P. Flanagan. But now the collapse of a wind farm has produced devastation: anglers fear irrevocable damage and a complete fish kill throughout the Mourne Beg river. They dread the destruction of crucial spawning grounds for salmonids, as well as losses throughout the Foyle catchment.

Local reporters pointed out the bitter irony of this unforeseen consequence of green energy tarnished, blackened, with the waters. The same day, a second bog slide occurred in Co.Kerry, near Mount Eagle; as it happens, Barrie Cooke illustrated some darkly disturbing monotypes of John Montague’s collection of the same name in 1985. An Irish farmer captured the Mount Eagle bogslip on video.

The Donegal disaster was discussed on The Mark Patterson show on BBC Radio Foyle, a few minutes before an interview devoted to the Barrie Cooke archive. You can listen to the entire episode here, or a recording of the interview alone, edited to remove signal drop (truly a sign of our times) by clicking the link below.

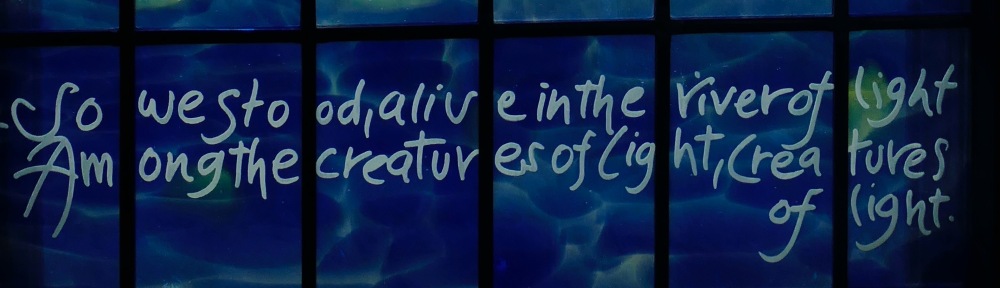

The interview mentions one hitherto little-known collaboration about water pollution between Seamus Heaney and Barrie Cooke, for an arts conservation fundraiser initiated in 2005. Heaney, ‘an apt pupil’ of Cooke and Hughes, whom he knew had been passionate activists in protection of what Hughes called ‘real water’ — water clear and healthy enough to support wild fish and their prey — was prompted to revisit the River Moyola, which used to flowed past the family farm and home of his childhood, Mossbawn ‘in the swim / of herself’. She was alive, only the seasons changing her, what Cooke called ‘actual vitality’:

her gravel shallows

swarmed, pollen sowings

tarnished her pools.

But that was before Nestlé opened a milk processing plant nearby in the 1950s. Then the Moyola was sullied:

Milk-fevered river.

Froth at the mouth

of the discharge pipe,

gidsome flotsam…

Barefooted on the bank,

glad-eyed, ankle-grassed,

I saw it all

and loved it at the time

Heaney would publish the whole poem in District and Circle (2006). But first he invited Cooke to supply a painting to go with it. Though the picture auctioned for charity is now in private hands, the Pembroke archive and collection contain two more paintings. Here is one of them — Cooke’s painterly imagination was generous and generative. It is a vivid response to that change in the river of life which his friend had witnessed as a small boy, and which he came to mourn in his maturity.

This was the latest in a series of paintings on the theme of pollution. Cooke had painted, and fought against, the horrifying beauty of polluted water since his first encounter with sewage on the River Nore. After he moved to a house above Lough Arrow in County Sligo in 1992, only to watch its extraordinary clear waters succumb to fatal eutrophication and algal bloom, he painted that too, and fought, successfully, to revive it.

Cooke would go on to observe and research the horrifying beauty of Didymosphenia geminata, documenting it in an exhibition and catalogue in 2007. He’d seen it blight both Irish and New Zealand rivers. Commonly known as ‘rock snot’, it is claimed not to endanger human health; this week’s comment by Invis Energy, the company that runs that Donegal wind farm, that ‘There is no risk to public health’, echoes this complacency. But Cooke, Hughes and their pupil in the fight for real water would surely have risen up against this latest outrage. In the introduction to the 1993 edition of his marvellous collection River, itself influenced by his and his son’s fishing adventures with Cooke, Hughes wrote: ‘Streams, rivers, ponds, lakes without fish communicate to me one of the ultimate horrors — the poisoning of the wells, death at the source of all that is meant by water.’

That too was the product of personal experience. A decade earlier, near the start of his own battle to save his beloved River Torridge from agricultural and industrial pollution, water abstraction, sewage, as well as the nets, he risked an expression of cautious optimism against the bottle-green gloom of algal eutrophication he was getting used to in periods of hot weather and low flows. Noting growing public concern at the way untreated sewage of Bideford rode up and down the estuary which the Torridge shared with the Taw, he saw ‘signs that the recently-discovered not to say revolutionary truth — what you pour down the drain reappears in your cup — is beginning to filter through.’

*

That was then, as Hughes was writing an essay on the Taw and the Torridge and their fish and their beauty for a book called Westcountry Flyfishing (1983).

This is now, after a year when some good news, in many rivers — a better salmon run than for years — has been tempered by new horrors. Corin Smith’s pictures capture, as he has done before, appalling suffering in the open-net salmon farms off the Scottish west coast. The mass escape from a salmon farm has led to devastating consequences for the genetic integrity of wild salmon stocks. The Environment Agency has provided new evidence of the profound ill-health of the waters of most of our rivers.

We now know that, for all Hughes’s fundraising and lobbying on behalf of the Atlantic salmon, and for all Hughes’s achievements in working with farmers and riparian landowners to found The Westcountry Rivers Trust, the source of the dozens of Rivers Trusts that have now sprung up around the world, we still have much to learn about the most urgent and effective ways of combating corporate industrial interests. In 1986 on the western coast of the Isle of Harris, Hughes was appalled by the sight of a boat full of salmon on its return to shore: ‘The layered loafed fish, and the netsmen, alarmed with what they had done, hushed, culprits.’ He also noted a newer threat: ‘Horrible atrocity scar of the smolt farm.’

We need to connect these local incidents, and what they, like man-made algae, have done to our waters and wild fish. Salmon farms promise to feed the world. Their owners respond to the complaints of passionate local activists by asking them for yet more evidence of what locals know has been happening to the fish in their rivers. This is indisputable and real. We also need a tool to provide that evidence, irrefutably, a tool which will allow all of us to make informed choices about the fish we buy in supermarkets and its origins. The salmon is still ‘owned by everyone’. It’s up to us to decide whether we carry on caging it, eating it, tainted with toxins, or find a better way to live with it and respect it and our own health.

But there is good news, for the future of wild salmon, wild rivers, and us. Such a tool exists. Our conference in Cambridge last December began with an extraordinarily powerful description of this tool by Will Darwall, who for eighteen years has headed the Freshwater Biology Unit at the IUCN, based at the Cambridge Conservation Initiative in the David Attenborough Building but with global reach. Freshwater fish, by their nature, swim under the surface. We need to bring their plight to light, wherever they swim, and in the case of the wild salmon, whatever marine and freshwater ecosystems they connect.

Please take the time to listen to Will’s presentation to the Cambridge conference

then refresh your memory of the Owned By Everyone conference programme, where you’ll find other talks. In his presentation Will describes the way the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species works. And make no mistake: it really does work. A recent reassessment of the eel demonstrates the huge power and influence it can have on policy makers, governments and thus on the businesses and multinationals corporations they regulate. Will’s salmonid subject case study here is a recent reassessment of global and sub-populations of sockeye salmon, which Ted Hughes fished for in the 1980s. But, a west country man himself, Will also refers back to Ted Hughes’s essay “Taw and Torridge”, with its own history of the decline in salmon stocks in his beloved rivers in the thirty years to 1983, and he brings us chillingly up to date. The numbers of wild fish caught in these rivers have dwindled. But then Will looks forward, longingly, urgently, to the real benefits that a reassessment of our own Atlantic salmon could bring.

To find out more about Salmon & Trout Conservation’s engagement with the issue, and their determination to raise the relatively modest funds required for that urgently needed reassessment by the IUCN Red List team, visit the S&TC home page. Or just visit their Virgin money just giving page. There you can make a donation yourself, however modest — big fish start in small eggs! — and learn more about ‘Owned by Everyone’s part in the conversations that led to this exciting initiative. Salmon & Trout Conservation prides itself on being ‘Science-Led. Action Driven.’ But it’s also, as it must be, culturally informed. The more inclusive, imaginative, and diverse the conversations we have about wild fish, the more we root them in local experiences and individual encounters (catch the excitement of one such meeting on the fast clear waters of a Welsh stream high above the River Tywi here), the more engaged and responsible our ways of caring for these extraordinary fish and their beautiful, mysterious habitats will be, and therefore the better our chances of protecting them and ourselves.

You’ll find out much more about all this in a new magazine, Wild Fish, which the OBE team in partnership with S&TC will be publishing online and in hard copy in the coming weeks.